Precision and monitoring feed required to hit targets efficiently

The European Chicken Commitment (Better Chicken) has added a new tier to live broiler production accreditation, which has the potential to increase the proportion of broilers considered slower-growing. For nutritionists, this means a change in focus depending on the growth rate, weight and age targets. Understanding each system and establishing key performance indicators is essential to optimize efficiency.

How slow can you go?

Across the global broiler industry, many tiers of production or accreditation schemes now exist, and a simple classification is as follows:

- Standard indoor production

- European Chicken Commitment (ECC) indoor

- Certified indoor production such as Chicken of Tomorrow concept in the Netherlands

- Winter Garden, Free-range, and Label Rouge with minimum slaughter ages

- Organic

Standard indoor-reared chicken is subject to country-specific or EU welfare regulations that stipulate maximum stocking densities. On-farm, the fundamental differences of the ECC scheme are that it focuses on a maximum stocking density (30kg/m2), enrichment and higher light intensity (50 lux). It does not stipulate a maximum growth rate but requires approved breeds assessed for welfare outcomes.

In the Netherlands, chickens produced to retailer aligned schemes, such as Chicken of Tomorrow, have been available for about six years. In the U.K., the equivalents are the animal welfare charity RSPCA Assured scheme for indoor production and the recently launched Red Tractor Enhanced Welfare label. Free-range production may be coupled with RSPCA Assured or Red Tractor Free Range standards and there are various organic accreditation schemes.

Feed for breeds

The RSPCA has assessed and approved breeds for use in its U.K. Assured schemes, which are also referenced in the ECC. They include Hubbard Norfolk Black, JA757 (pictured), JA787 (pictured), JA957, JA987 or Rambler Ranger, Ranger Classic and Ranger Gold.

James Bentley, global technical director for Hubbard, explained that “for fast-growing breeds producing nutritional recommendations is relatively easy. There are lots of flocks on the ground, so lots of data to learn from, and although each flock has a set target weight — if they get there a day or so early, it’s manageable and may reduce costs. You can identify optimum nutrient levels in terms of energy and amino acids levels, etc., which can be applied across many farms and companies even globally.”

“It becomes more complicated with slower-growing production. At one end, you have organic production with minimum slaughter ages of 70 to 81 days or Label Rouge (with) maybe up to 90 days — although in these cases, there is more experience of what suits local conditions. In between these and standard production, you have free-range slaughtered at around 56 days, assured indoor and now ECC. It is much harder to make general recommendations as there is greater local variation in management and housing systems. Target weights will also depend on region, assurance scheme and seasonal changes in the market.”

According to Bentley, one challenge for free-range producers is that EU marketing regulations dictate that birds cannot be slaughtered before 56 days. If they require a target body weight at 2.3kg, but the birds grow faster and reach 2.5kg, they couldn’t slaughter them earlier and may not be able to recover the value of the additional weight.

“The feed program used must adapt to this situation,” he said. “For ECC, it may be more straightforward, as there is no minimum age or maximum growth rate and each producer may apply their own constraints.”

More time to act

With a slower-growing chicken, there is the luxury of time.

“You are able to be more dynamic with your feeding program for each flock. Whereas for a standard broiler, you have set diets and little time to react and make changes. A longer growing period means there may be time to react,” Bentley said.

Here is where bird weighing and performance monitoring is fundamental.

“Setting Key Performance Indicators — for example, 24 days in free-range systems — gives producers the ability to make changes to the age when diets are changed, the feed form and nutrient content,” he said.

Because of this, Bentley suggests that regular weighing, careful performance monitoring and communication with the nutritionist are essential.

“This way you can adjust formulations and ration changes to speed up or slow down growth to achieve the target,” he said. “There are different strategies, but producers may decide to stay on the starter or grower ration for longer if the birds aren’t at the target weight. Another option is to move to a mash diet after 28 days to slow down growth rates or add whole grain.”

Where whole wheat is added to the diet, which is common in the Netherlands, there is the possibility of altering the inclusion rate to dilute the diet.

Regular weighing, careful performance monitoring and communication with the nutritionist are essential. (Hubbard)

Regular weighing, careful performance monitoring and communication with the nutritionist are essential. (Hubbard)Nutritional differences

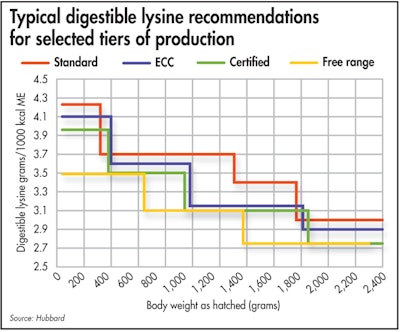

While making general recommendations isn’t straightforward, Bentley highlighted some general principles: “As the birds are growing for longer, the amino acid specifications don’t need to be as high. Overall, diets are lower in both protein and often in energy, following the same pattern of reduction with bird age.”

Many producers will still use a similar regimen of three diets (starter, grower and finisher). However, a fourth may be added to create a finisher 2.

Hubbard’s typical digestible lysine recommendations for selected tiers of broiler production. (Hubbard)

Hubbard’s typical digestible lysine recommendations for selected tiers of broiler production. (Hubbard)“Some producers have two different finisher rations available, with different energy, protein and amino acid specifications,” he said. “Then they can choose which to feed depending on how the birds are growing or the target weight customers have requested. The season may have an effect on slower-growing chickens, particularly if they are in open or free-range housing, due to the energy required for maintenance.”

Andrew Fothergill, national poultry advisor, ForFarmers U.K., added: “Raw materials used are broadly similar — there being some opportunity to utilize less nutrient-dense ingredients where lower nutrient-dense diets are employed, depending on the breed used and its genetic potential.”

However, certain schemes have requirements for the birds to be fed a minimum level of cereals or include at least two or three types of cereal. There are also local variations; for instance, in France, they will use a lot of sunflowers and any corn-fed brands will have minimum corn inclusions. Many labels/brands are also linked to other sustainability aims. Soy may have to come from an assured source, local ingredients used or guarantee of antibiotic-free.

Slow growth production may cost more in terms of efficiency, but the cost may be matched by the monetary value of improvements in welfare and sustainability. (Hubbard)

Slow growth production may cost more in terms of efficiency, but the cost may be matched by the monetary value of improvements in welfare and sustainability. (Hubbard)The future is slow

Summing up the challenges of feeding slower-growing chickens, Fothergill said, “the biggest driver of feed conversion efficiency is growth rate — the greater the amount of growth that can be delivered per unit of maintenance energy, the lower the cost of production. The efficiency of digestion of nutrients does not differ greatly between breeds, but for maximum daily growth rate standards, the efficiency of feed conversion is significantly impacted.”

When you talk about this change in broiler production, the question a nutritionist must ask is how slow you want to go. For each of these schemes there is a cost in terms of efficiency, which much be matched by the monetary value of improvements in welfare and sustainability.

By 2026, it seems clear that a higher proportion of the broilers in Europe and the U.S. will be grown under stricter welfare standards. Bentley concluded that this means a change in focus for nutritionists.

“Instead of wanting to reach target weights quickly and efficiently — they also need to assess how to meet specific growth and welfare targets as environmentally sustainable as possible,” he said. “It is essential to know how the birds are performing so that you can finetune nutrition and management. Precision nutrition will be the order of the day and the least cost on its own may become a thing of the past.”